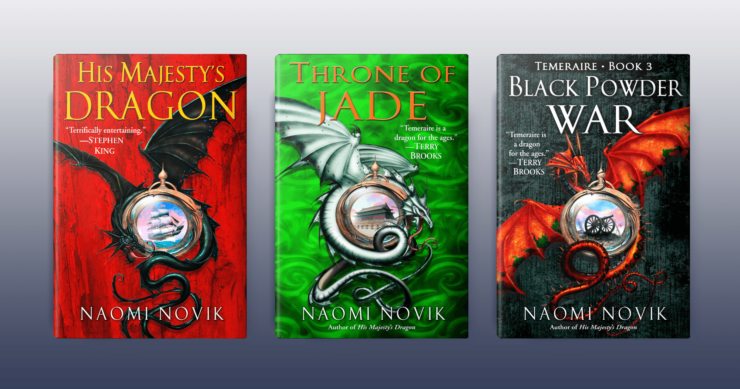

I came late to Naomi Novik’s celebrated series. I’d heard of it, of course: it was a huge bestseller, and everyone was talking about it. By the time I worked my way down to it in the TBR pile, the epic was five or six volumes in. On the one hand, late to the party. On the other: marathon read!

I’d known from the beginning that I had to at least try it. Patrick O’Brian meets Anne McCaffrey—that’s two of my favorite fandoms intersecting. Not to mention the spirit of Jane Austen wafting over it all.

There’s always a worry when a younger author pays homage to the Great Old Ones. Will it work? Will the homage come up to the expectations of its lineage? Bestsellerdom is no guarantee. Lord knows how much Jane Austen fanfic has topped the lists, purely because of Austen’s name. Some of it is actively painful to read, if one has any sense of the original at all.

Fortunately Temeraire’s series, like the dragon of that name, has bred true. It’s the real deal. It not only gets it right, it does so through nine volumes.

It starts off pretty much where Patrick O’Brian’s Aubrey and Maturin series does, with a British Naval captain during the Napoleonic Wars. We meet Captain Will Laurence on the deck of his ship, fighting the French. He wins the battle and the prize, a ship that carries unexpected and disconcerting cargo: a dragon’s egg.

This is a world full of dragons. They’re numerous in the wild, and they’ve been domesticated for use as weapons of war. From Laurence’s perspective however, the Aerial Corps is very much inferior to the Navy or even the Army, and aviators are a universally despised class. To be an aviator is to be a kind of outcast.

But dragons are tremendously valuable to the war effort, and a dragon’s egg is a major prize. This egg is perilously close to hatching, but the ship is weeks away from any dragon covert. Someone on board will have to harness the hatchling immediately or, Laurence is assured by the ship’s doctor, the creature will escape and go feral. This cannot be allowed to happen. Britain needs every dragon it can get.

It’s an unhappy situation. Laurence knows his duty, as distasteful as it may be. He gathers his officers to draw lots, and the loser will harness the dragon.

Buy the Book

The Keeper’s Six

Or at least that’s the plan. As often happens in war, the plan does not survive engagement with the enemy—or in this case, a very young, very articulate, very self-willed creature who has no use for the terrified and effectively helpless would-be dragon-tamer. Laurence has no choice but to do it himself.

He knows what this means. He’s killed his naval career. He’s pretty completely shut down his relationship with his father the Earl, who is already less than thrilled with Laurence’s original choice of occupation. He’s sacrificed his entire future for the hatchling who requests that he give it a name; rather in desperation, Laurence calls it Temeraire, after a famous ship of war.

What begins as a grudging sacrifice and a great comedown in the world transforms gradually into a profound and lifelong bond between man and dragon. Laurence is a man of unshakable integrity and unflinching honor. He does his duty no matter what the cost. But he is also a person of deep feeling, and he comes to love Temeraire as a fellow sentient being.

At first no one on the ship even knows what kind of dragon this is. When Laurence has occasion to consult an expert, he’s told that this is a rare and valuable Chinese breed, an Imperial. But as Temeraire matures, it becomes clear that he’s something far rarer still. He’s a Celestial, one of the tiny handful of dragons reserved exclusively for the royal family of China.

In the meantime Laurence goes into training as an aviator. He takes a crash course in dragon handling and aerial warfare, learns the secrets of the service into which he has so reluctantly fallen, and fairly quickly is thrown into combat against the armies of Napoleon. He also discovers Temeraire’s draconic gift and inherited talent, which is called the divine wind: a sonic wave that can flatten trees and bring down mountains and sink ships.

Laurence and Temeraire’s journey of discovery spans the whole world. The core of it is the war against Napoleon, and the role that dragons play on both sides. Laurence is tremendously loyal to his country, but his strong moral compass sometimes brings him into conflict with Britain’s politics and its politicians.

The more he learns about dragons, the more his allegiances shift. What at first he perceived as ferocious and dangerous, barely conrollable animals turn out to be thinking beings. Some, like Temeraire, are more intelligent than most humans, and more erudite and better read as well.

By the time the series concludes, it’s taken us from the high seas to Great Britain to China, along the Silk Road to the Ottoman Empire, all over Europe, to Russia, to the Americas, to Australia—when Laurence is transported for treason—and to Japan. Laurence and Temeraire serve as a catalyst for change, not only to bring down Napoleon, but to make great strides for the rights of dragons in Britain. Dragon laborers on equal footing with humans, drawing wages. Dragons in Parliament.

There are hundreds of species, of all sizes and shapes, with all sorts of talents and attributes. Dragons that breathe fire. Dragons that spit poison. Dragons so huge they can only live in the sea. Dragons whose scales take almost the shape of feathers.

This is worldbuilding on a truly grand scale. Nor is it just about taxonomy. The effect of dragons on history, their use in war, is detailed and intricate and thought out down to the minutiae of supply lines and the challenges of feeding legions of giant predators.

The worldbuilding itself is amazing, the meticulous research, the weaving of dragons and their capabilities into historical war and politics. What brings it truly to life is the cast of characters. Laurence and Temeraire are a wonderful pair, fully as much so as O’Brian’s Aubrey and Maturin, and they’re supported by a host of greater and lesser characters.

I’m particularly fond of Jane Roland, the fighting captain whose existence at first appalls the very traditional, patriarchal Laurence. Hammond the diplomat is a slippery and frequently exasperating personality, but he’s always interesting. Tharkay the spy is complicated and mysterious and ambiguous in his loyalties. Napoleon is a malignant narcissist and a monomaniac and he can be brutal and ruthless, but he can also be charming and considerate and even empathetic.

The dragons more than hold their own among the human characters. Huge, loyal, phlegmatic Maximus; fiery and opinionated Iskierka; the Japanese river dragon who is almost a goddess, and irresistibly amiable; lovely Mei and terrifyingly pragmatic Ning. The white dragon Lien is evil, but she has reason to be. We can sympathize with her even while we hope she fails completely in her campaign of vengeance against Laurence and Temeraire.

This is one of the great alternate-historical series of the new century. What puts it over the top for me, along with all of its other significant virtues, is the prose. It captures the essence of its period. The language, and the mindset behind it, the world view that informs all of its characters and most especially Laurence, is pitch-perfect. I really did feel, as I read, that I had been transported to the world of the early nineteenth century—with dragons. So. Many. Dragons.

Judith Tarr is a lifelong horse person. She supports her habit by writing works of fantasy and science fiction as well as historical novels, many of which have been published as ebooks. She’s written a primer for writers who want to write about horses: Writing Horses: The Fine Art of Getting It Right. She lives near Tucson, Arizona with a herd of Lipizzans, a clowder of cats, and a blue-eyed dog.